In the wake of the French Revolution, Parliament saw protest as potentially treasonous. The poor could achieve justice through the courts, in theory. Legitimate power lay with government agencies, not with the people. Magistrates viewed protest as an attack on lawful authority, whatever the cause.

Britain’s war with Napoleon damaged trade, and brought economic recession. Unemployment, poverty and food shortages led to protest, often out of desperation. Anger energised and distorted valid concerns for justice.

In 1813, two men attacked the home of a wealthy lace manufacturer, John Boden. The Leicester Chronicle called the men criminals: Loughborough is infested with thieves and predators. It also related their crime to: the extreme distress now generally felt. Perhaps the men’s ‘wickedness’ was a protest against hunger? As for Boden, he had loaded pistols to hand. The housebreakers fled.

At the bottom of the social scale, Sarah Monks protested against the expectations of Rosliston’s workhouse. When the master told her to get on with her jobs, she refused and was rude. So, the master took her to court. The Law took no interest in Monks’ health, situation or feelings. It criminalised a protest we might think reasonable.

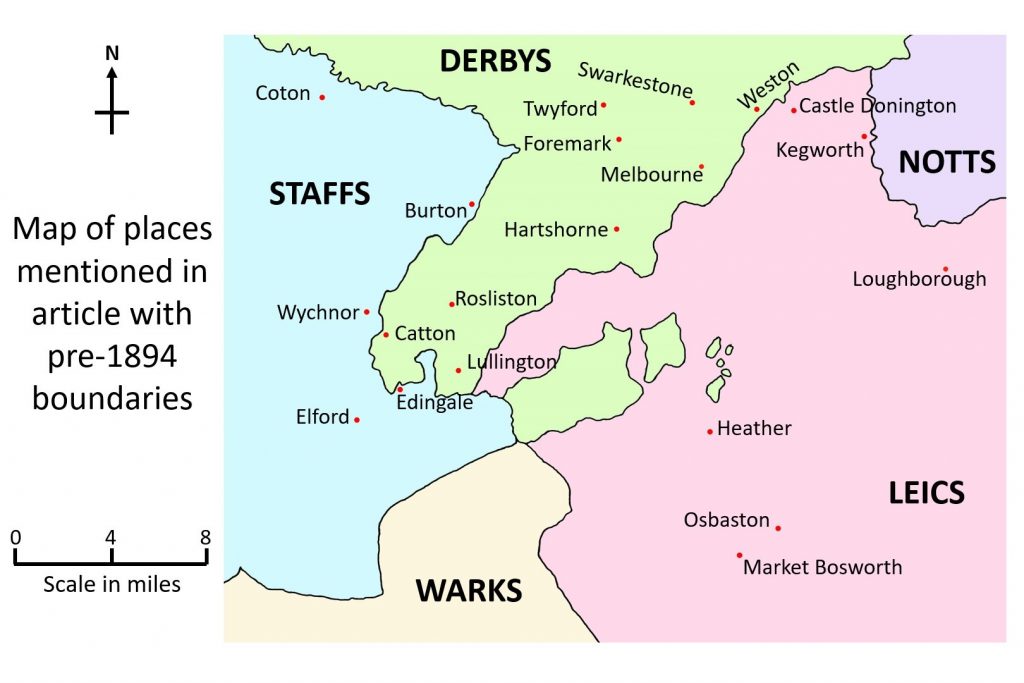

So, let’s look at protest in an area of the Midlands during and after the French War. This will include an armed raid on Boden’s lace-making factory, and problems caused by false rumours.

1.Hunger Protests in Midland Towns

Alrewas parish registers describe the winter of 1794-5 as especially harsh. With sixty days of frost, the rivers Trent and Tame froze over. Mills couldn’t grind corn. Then, a sudden thaw brought floods. Whether local stocks of grain were damaged or transported elsewhere, bread and flour grew scarce. At Alrewas mill people gathered in riotous mood. In Hinckley, Atherstone and other Midland towns, protest erupted. In each case, authorities asked the militia to restore order.

Many riots sprang from hunger, plus rumours of middle-class unfairness. When food prices rose sharply in 1800, the poor suspected farmers of hoarding grain to get a better price later. Some farmers experienced abuse when they brought corn to market. Magistrates tried to quell ill-feeling by asking them to sell wheat at lower prices. One Friday at Derby market, Weston-on-Trent farmers tried to push every seller of wheat into reducing their price.

Suspicion of farmers extended to all who sold food, especially bakers. At Nottingham in April 1800, a mob destroyed carts and market stalls. Many ran off with butter, potatoes and meat. In August, protesters attacked bakers’ shops. By the time soldiers arrived, men had seized corn from barges on the River Trent, and distributed sacks of it to women and children.

Magistrates tried to increase fairness by regulating the cost of bread. They met weekly in county towns to raise or reduce the weight of a penny loaf according to the price of wheat. Not all complied. Two Melbourne bakers sold loaves below the weight set by the Derby assize. A Kegworth butcher, caught out by paid informers, was convicted for using false weights.

Such cases inflamed local gossip. In a riot at Stafford, the mob smashed a baker’s windows and broke into his house. Terrified, one inmate seized his gun, fired it into the crowd, and wounded three people. The magistrates enforced peace with a troop of Light Dragoons.

2. Protest in Rural Communities

Revenge Attacks

On Plough Monday 1804, eight labourers visited farms between Elford, Edingale and Catton. January weather meant reduced employment, and custom demanded ale and a tip for a simple entertainment. Two Elford farmers refused. So, the men wrecked their gravel roads with the decorated plough they’d dragged along for the show.

Payback for wrongs, whether real or imagined, could be petty or deadly. One evening in 1813, farmer John Darlaston of Elford was relaxing in his living room. He’d closed the shutters, but someone saw enough through the window to shoot him. A doctor removed several slugs from Darlaston’s head.

Why did assailants feel so strongly? Evidence is limited but sometimes it’s possible to form an opinion. For example, John Levett of Wychnor Hall cleared part of the village to expand his park. His nephew, Theophilus Levett, inherited the estate in 1799. When he discovered John Nicholson taking his game, he told him to keep out. Nicholson then wrote to Levett, threatening to kill him. His grievance possibly stemmed from the Levetts removing his right to access former common land. Anyway, in 1814, the 36-year-old Nicholson found himself in court. Levett paid for his defence lawyer and recommended him to mercy. Thus, Nicholson became a convict, bound for Australia.

Poverty, harsh treatment, and festering grievances lay behind revenge attacks. Nevertheless, they rarely came to court. Even in the hunger protests of 1800, the number of farmers who experienced significant loss was relatively small. A fire set at John Briggs’ farm in the parish of Melbourne, spread to his house. Neighbours helped him save corn and hay and most of his furniture. The Melbourne Estate replaced the buildings. Again, two farmers at Twyford awoke to find stacks of wheat on fire, while at Coton-in-the-Clay an arsonist fired Ralph Adderley’s barn. Adderley lost oats, beans and wheat worth £200, and claimed compensation from his Hundred, a local administrative area. The judge supported his claim, and considered him a victim of protest against high food prices.

Theft of food: Survival or Greed?

Was theft of food a form of protest? For example, Francis Lakin feloniously milked a cow at Rosliston in 1817. Perhaps he or his children needed nourishment. Maybe he often squeezed udders at night for a buyer. Either way, his crime doesn’t look like a protest; it offers no evidence of disapproval or grievance.

In 1817, Joseph Bagnall and William Watson stole two turkeys from Sarah Smith’s farm at Lullington. Both spent a year in prison. Bagnall returned to the village and his growing family. Claiming poor relief, he received four shillings a week, less than half a labourer’s wage.

Meanwhile, Watson received bacon, bread and candles stolen from Lullington farmer, Thomas Moore. Following another six months in gaol, Watson applied to the vestry for relief.

Watson and Bagnall lived in Lullington, committed crimes there, and then settled back into village life. Clearly poverty lay behind their offences, yet evidence of protest is missing. They seem to have used an opportunity to gather a few good meals.

Contemporaries believed thefts increased during and after the War with France. However, few records of minor offences exist, and cases which went to court don’t reflect the scale of the problem. Many thieves got away with it.

During the 1790s, farmers and landowners formed local societies for the prosecution of felons. One in the Swarkestone area offered fifty guineas to men who’d watch the pastures of its members and secure convictions for sheep stealing. Farmers marked heads and fleeces, but most thieves skinned a sheep and cut off its head before taking the carcass home. Thus, they evaded detection, and farmers felt the loss.

In 1800, William Tew took three sheep from farms at Foremark and Hartshorne. Initially condemned to hang, the judge later banished him to Australia. As for his crime’s motive, it’s scale suggests profit more than desperation.

3. Protest to Defend the Vulnerable

Crimes involving cruelty, cried out for censure. So, what muted protest on behalf of abused children?

In 1797, James Adams of Market Bosworth employed five girls as apprentices, three from Coventry, one from Heather and one from Osbaston. They combed raw wool, and wound the bobbins for Adams’ knitting machines. No one looked out for them, so they were probably orphans. They brought Adams money from Poor Law authorities, but he showed minimal concern for their welfare.

Adams’ apprentices wore rags, and craved food. He gave them coarse barley cakes, but little else and not enough. At night, the girls slept in a room with no glass in the window, and just a thin blanket. Their bed was the floor, with not even a mat.

When the girls made mistakes, Adams beat them. Neighbours heard shrieks of pain, and saw the bleeding wounds. Some dressed the girls’ injuries; their compassion awakened. Yet they failed to expose Adams’ abusive behaviour.

The neighbourhood’s lack of protest suggests hopelessness and resignation among the labouring poor. Maybe they felt no action of theirs would make a difference, or that if they complained they’d risk their own welfare. And though Adams’ treatment of the girls shocked neighbours, many people experienced poor working conditions, albeit of a less severe kind.

Eventually, neighbours reported Adams and his son to Market Bosworth’s parish officers. Alerted to such heartless behaviour, magistrates acted swiftly. They released the children from their apprenticeships, and prosecuted the Adams with as much rigour as the Law allowed. The Derby Mercury expressed revulsion, but failed to record the Adams’ punishment.

In the next two stories, we’ll consider protest on behalf of industrial workers. I’ll discuss these in detail to show how different movements in society reacted to each other.

4. Business Man Outraged at Castle Donington

A factory destroyed

News enthusiast Simon Orgill knew about industrial protest around Nottingham, but didn’t suspect he’d become one of its victims. He ran a small lace making business in Castle Donington and considered himself a fair employer.

Orgill lived next to the old farm buildings which housed his warp frames. Minutes after midnight on 11th April 1814, men raided his factory and tried to set it ablaze. They smashed Orgill’s machines and ruined his lace.

The noise of hammers breaking wood within feet of the house propelled Mrs Orgill out of bed. She threw open the window to peer into the night. She then heard a shot, and felt the bullet pass by her.

As the wreckers poured out of Orgill’s yard into Borough Street, one shouted: Old Simon! Before we go, I’ll have another peg at you!

Immediately, shot from a musket shattered the bedroom window. Shaken but uninjured, the Orgills ventured outside to inspect the damage. Later, the Nottingham Gazette reported the event from Orgill’s perspective.

Workers’ Feelings

Orgill’s factory became a target of violent protest due to his fraught relationship with ex-employees. Despite the efficiency of Orgill’s machines, he couldn’t compete with a depressed lace market. He could either store products in hope of better times, or sell them at a low price.

In 1813, Orgill’s workers demanded an advance in wages and he refused. Later, he sacked five men for drinking and playing cards round the stove for hours at a time. Orgill thought them lazy, but their behaviour probably reflected a low demand for lace. Employers paid hands, not for their time, but on the basis of the price they got for their products.

Unemployed framework knitters had little hope of finding work. One discarded man reacted with anger. He told Orgill: You’ll be the loser! Another begged Orgill to re-instate him. Orgill said: Yes, but only after you’ve worked somewhere else for a while.

Tom Oldershaw found work as landlord of the Turks Head. Orgill made peace with him, and soon favoured his pub for its beer and newsroom. Oldershaw said: Orgill’s hands get good wages and working conditions. They could earn 66 shillings a week, roughly five times the wages of an agricultural labourer. On the other hand, take home pay declined when demand for lace fell.

By May 1814, Orgill’s factory functioned with eleven machines, as before the attack. Then, an undisclosed pressure group tried to persuade Orgill’s employees to quit their jobs. Eleven men, probably persuaded by Orgill, wrote to the Nottingham Gazette: We are satisfied with our employer, employment and prices.

Political Protest

In addition to ex-employees with a grievance, Orgill faced a more secretive force. To understand it, let’s consider events in Castle Donington the day before the attack.

An old acquaintance of Orgill’s met him at the Bell and Crown on 10th April. John Blackner edited the Nottingham Review, a newspaper with radical leanings. Orgill liked its principles, and distributed copies in Castle Donington. As an individual, Blackner admired revolutionary France, hoped Buonaparte would bring Europe liberty, and wanted to abolish England’s gentry. Orgill dissented from some of this but enjoyed a spirited debate over a pint.

Later, Blackner accepted an invitation to take tea at Orgill’s house. He seemed agitated, and in Orgill’s garden appeared to survey the factory. The two men then visited the Turk’s Head. Orgill returned home at 10.00 pm.

After the raid, Blackner seemed indifferent to Orgill’s loss. In the morning, Orgill found wadding from guns fired at his window. It consisted of fragments from the Nottingham Review.

Soon, Orgill’s growing suspicions hardened into a feeling that Blackner hated him. An acquaintance told him about two of his former workers. They’d met Blackner in Nottingham to discover more about the frame breaking.

Thus, two volatile characters began a furious correspondence in the Nottingham Gazette. Orgill now felt the Review offered excuses for breaking knitting frames. He accused Blackner of treason, of inciting rebellion against the British constitution. So, Blackner called Orgill a liar, and a tyrant to his employees. The two men pushed each other into a need to justify themselves in the eyes of the public.

A Chance for Compensation

Orgill claimed compensation from his Hundred. Rate payers opposed his claim. In 1815, a jury at the Leicester Assizes decided in his favour. The judge awarded him £400. Probably, he’d secured a loan for new machines on the basis of receiving damages.

The Hundred appealed to the Court of King’s Bench, which tried the case in 1817. The issue hung on whether Orgill’s lace frames were engines within the meaning of the relevant Act of Parliament. Although fastened to the floor, his machines had no connection to the soil. Thus, Orgill lost his case. His business suffered, but survived until 1829.

Orgill may not fit our view of a typical factory owner, and his story leaves us with unanswered questions. Who smashed his machines in 1814? Was Blacker leading an illegal union of framework knitters? Were supporters of the middling sort helping such a union protest against poor working conditions? A wealth of rumour and suspicion boiled down to poverty of evidence. No prosecutions took place.

The next story considers protest against factory owners from the perspective of those who caused the damage. It answers the broader questions which Orgill’s tale leaves hanging.

5. Protest at Loughborough

Factory Workers on Strike

Heathcote and Boden’s factory at Loughborough boasted fifty-five warp frames, compared to Orgill’s eleven. Apprenticed to a framework knitter at the age of 14, John Heathcote invented a machine which imitated the actions of a lace maker’s fingers. His technological improvements threatened the livelihoods of workers who used less cost-effective methods.

Few could compete with Heathcote and Boden’s prices, yet even they experienced a slide in profits as the Napoleonic war came to an end. In May 1816, they reduced their workers’ wages.

Heathcote employed four hundred men, women and children. Informed they must labour for less, they walked out. Struggling to survive, most returned to work under the new conditions. Heathcote sacked suspected ringleaders, and resentment lingered within the town.

Preparations for Protest

In June 1816, a few of Nottingham’s leading Luddites recruited men to help them smash Heathcote’s machines. Adopting a mythical leader, Ned Ludd, this tight-knit group of textile workers used terror tactics to persuade employers to give framework knitters a fixed price for what they produced.

Luddite William Withers had £18 to buy hatchets and pistols for the Loughborough job. He also held £46 to pay Old Neds who made the attack. Another recruiter promised £5 each plus expenses to all who helped. He offered strong motivation for a venture which involved great risk.

Many of the gang were friends or family members. Jem Towle had some work on his hand frame to finish, but his brother Bill said they needed him for this really strong job. Again, Withers’ brother-in-law, Christopher Blackburn, agreed to go, as did Christopher’s brother John. Aged 32, Withers had a wife and daughter. He said extreme poverty drove him to Loughborough.

Anxious to avoid suspicion, seventeen Old Neds left Nottingham singly or in pairs. Four spent the evening of 28th June at Loughborough’s Seven Stars. The evening was warm, but one wore his coat to hide the pistols. Perhaps feeling safe among sympathisers, Bill Towle performed a song with the chorus: Damn such laws, and so say I.

At midnight the gang assembled in a dark lane near Heathcote’s factory. Thomas Savage passed round a quart of rum. Then, with hopes of misleading those who saw them, the men changed clothes with each other and put handkerchiefs over their faces.

A Violent Attack

As the Luddites advanced, they spied one of Heathcote’s men returning from supper. They seized him, clapped a pistol to his head, and told him to let them in without raising an alarm. Then, as they crept into the factory yard, a guard dog snarled. Jem Towle shot it, and it barked no more.

Suddenly, the casting shop door sprang open. Armed Luddites entered, and saw three nightwatchmen sitting on stools. One guard reached for a pistol, presented it and pulled the trigger. In his haste, he failed to cock it.

John Blackburn saw the man aim a pistol at his brother. He fired, and John Asher fell to the floor. The ball struck the back of Asher’s head but didn’t penetrate his skull. When he regained consciousness, a Luddite said: If you stir, I’ll blow your brains out.

As the gang moved through the three-storey building, they secured Heathcote’s employees on each floor. One guard had no intention of letting invaders into his room. His four comrades, however, feared for their lives. They heard a Luddite call out: Advance with the blunderbusses! So, they all surrendered. Ordered to prostrate themselves with faces to the floor, they obeyed.

As he viewed rooms full of lace frames, one Luddite shouted: Ned, do your duty well; it’s a Waterloo job!

For forty minutes, Old Neds hacked and hammered Heathcote’s machines to pieces. They made an horrific din. On their way out, they told Heathcote’s men: Tell us of any machines working under price, and we’ll break them.

After the Party was Over

As they ran into Ashby Road, one Luddite counted up to ninety in a loud voice. They wanted to convince the neighbourhood of their numerical strength. The Leicester Chronicle bought into this. It believed thirty Luddites wrecked the factory, while fifty stayed outside to smash its windows and warn neighbours to keep indoors.

Taking an indirect route back to Nottingham, the Luddites crossed the river by ferry at Radcliffe-on-Trent. Here they took off their disguises and separated. Hours later, two of them met Thomas Savage at a public house, where he paid them ten shillings each. When Bill Towle promised £5 each, he’d exaggerated.

Back in Loughborough, constables arrested suspects. In Nottingham, the police searched houses. And the London Gazette offered five hundred guineas for information leading to convictions. Beyond the vandalism, authorities feared Luddite political influence. Desperate to secure information, they aimed to crush radical activists and Nottingham’s alleged union of framework knitters.

Aware of threats to his business, Heathcote had toured Devon in 1815 with a view to re-locating. He now bought a mill at Tiverton and converted it to lace manufacture. Thrown out of work by the Luddite attack, a hundred or more Loughborough families walked to Tiverton. Heathcote became a Member of Parliament, and gained a reputation for providing employees with good housing and education.

Luddites Tried and Convicted

By January 1817, fifteen men involved in the Loughborough raid were in prison, awaiting trial. Arrested for poaching and attacking a gamekeeper, John Blackburn offered magistrates a deal. If they let him and his brother escape punishment, he’d tell them everything about those who destroyed Heathcote’s factory.

In March, twelve Luddites faced trial at Leicester Assizes, charged with shooting John Asher. Juries feared public hostility to a death sentence reached on the basis of frame breaking. The charge of attempted murder shows the Crown’s determination to make an example of those found guilty.

On 24th April 1817, with some Luddites already dead, a military escort accompanied six men to Leicester’s place of execution. Several thousand gathered to see the spectacle.

Thomas Savage, who had a wife and six children, bowed to the crowd. He said: I’m grateful for the religious instruction I received in prison. My sentence was just; my ruin stems from my neglect of the Sabbath.

A newspaper reporter thought most of the men indifferent to their fate rather than repentant. As John Amos said to the crowd: Yes, we all broke machines, but none of us shot John Asher.

On the scaffold, the men sung a hymn. The hangman then launched them into eternity. And society breathed freely; the crowd did not riot.

Funding for Luddite Attacks

Once caught, several Luddites willingly answered questions from magistrates. According to Jem Towle, Old Neds had no common fund, and no formal connection to the middling sort. When they decided on a job, they visited working framework knitters and asked for a small contribution. If anyone refused, they dug up his potato patch or smashed his frame. Money to wreck Heathcote’s factory came from Loughborough’s lace workers.

Thomas Savage offered magistrates an alternative view. He incriminated Nottingham manufacturer, Frank Ward. He thought Heathcote’s competitors paid Ward £100 to arrange the attack. If true, how likely was Savage to know this?

Formerly a lace hand himself, Ward had laboured to become a master with ten men. When trade declined, he refused to reduce his workers’ wages. Later, he believed some arrested for Luddite acts were innocent. So, when a few masters agreed to raise funds for a defence lawyer, Ward became their treasurer.

On the basis of Savage’s statement, magistrates suspected Ward of stirring up revolution. In February 1817, Parliament had given authorities a right to discard normal legal processes in cases of suspected of treason. Thus, on 10th June, twelve police officers searched Ward’s premises without a formal warrant. Finding no seditious documents, they arrested him anyway and threw him into a damp cell. Later, constables took him to London in chains.

Released in November, Ward was never formally charged with a crime. He returned to Nottingham to find his wife ill, his business in tatters, and himself described in a newspaper as a Luddite member of a secret committee.

Ward protested against this libel, and in 1819 the Court of King’s Bench awarded him £600 in damages. For magistrates, Savage’s view seemed to confirm their suspicions of a framework knitters’ trade committee aided by middle class allies. Apart from the implausibility of Savage’s claim, Luddism and its connection with radical politics seem loosely structured. In spite of informers and infiltrators, evidence of an organising committee remained elusive.

Writer’s Thoughts

Protest and Ethics

Regency England feared public gatherings to express dissent from the status quo. Forms of protest were yet to evolve into those of a modern democratic society. In theory, anyone could make a complaint through the courts. In practice, the poor either surrendered to their situation or lashed out. While protest could include a sullen attitude to authorities, discussion needs to follow the evidence. Thus, I’ve defined protest as outward expression of disapproval. This includes both actions to bring about change and revenge attacks by individuals.

In principle, authorities accepted protests which sought settlement through negotiation. They labelled those who acted with violence as rascals or bad characters. Certainly, protestors broke the Law, yet the values of Luddites included a concern for justice. Moral principles motivated their actions, in part at least. We may dissent from many of their actions and values. I’m not saying they behaved rightly or wisely, only that the relationship between crime and morality is complex.

Poverty and Politics

Behind much thieving and violence lay personal poverty. Some felt they had no other direction in which to turn. Miserly Poor Law payments and a repressive social environment fostered disobedience. Desperation drove protests in which self and family, of necessity, featured more strongly in the minds of the poor than concern for social justice. And yet, a majority did not protest. Most settled for quietness and sobriety, whether from fear of making life worse for themselves or because they found ways to survive.

Luddites and radicals of the middling sort demonstrate a political aspect of protest. William Burton, who took part in the Loughborough job, toured villages to sell radical pamphlets. Luddism applied French revolutionary tactics to their trades’ dispute with employers. At one level, authorities acted weakly, advising the poor to trust in the Law and charitable individuals. At another, they became more coercive, eroding their claim to act justly. From the point of view of protestors, violence seemed their only hope of success.

Stories of crime and protest reveal tensions and fissures within society. Britain’s wealth poured into war meant economic recession at home. New technologies spelt success for some but reduced circumstances for those who couldn’t compete. And all classes lived in fear, whether of disorder or hunger. Society needed to work better, and struggled to do so.

Leave a Reply