Farmers work the land we see through a speeding car window. Their homes and barns, plus the secrets of their way of life, pass quickly by us. This article focusses on the work and lives of South Derbyshire farmers in the early nineteenth century.

In 1807, a group of agricultural reformers asked John Farey to survey Derbyshire farms. A growing population with many employed in industry, needed more food. What could England learn from farming practices to the south of Derby?

Meticulous and energetic, Farey had experience as a land agent and geologist. With no regular salary, he needed commissions to support his family. So, Farey spent two years on his Derbyshire field work, then published his findings in three volumes.

Farey did not portray Derbyshire’s agriculture as a whole. He limited his interest to large, well-managed farms. He examined practices which made the most of land and crops. Thus, he gave a partial view, though it reflected a trend towards draining land, crop rotation and selective breeding of livestock. Such methods increased productivity.

Many farmers preferred old ways, couldn’t afford improvements, or lacked ambition. An 1816 survey of fifteen South Derbyshire farms rated six farmers as outstanding managers and five as reasonable. The remainder made poor use of their resources. For example, the surveyor thought the state of land and fences on Sarah Smith’s 180 acres at Lullington deplorable. As for Farey, he had no time for farmers he considered backward.

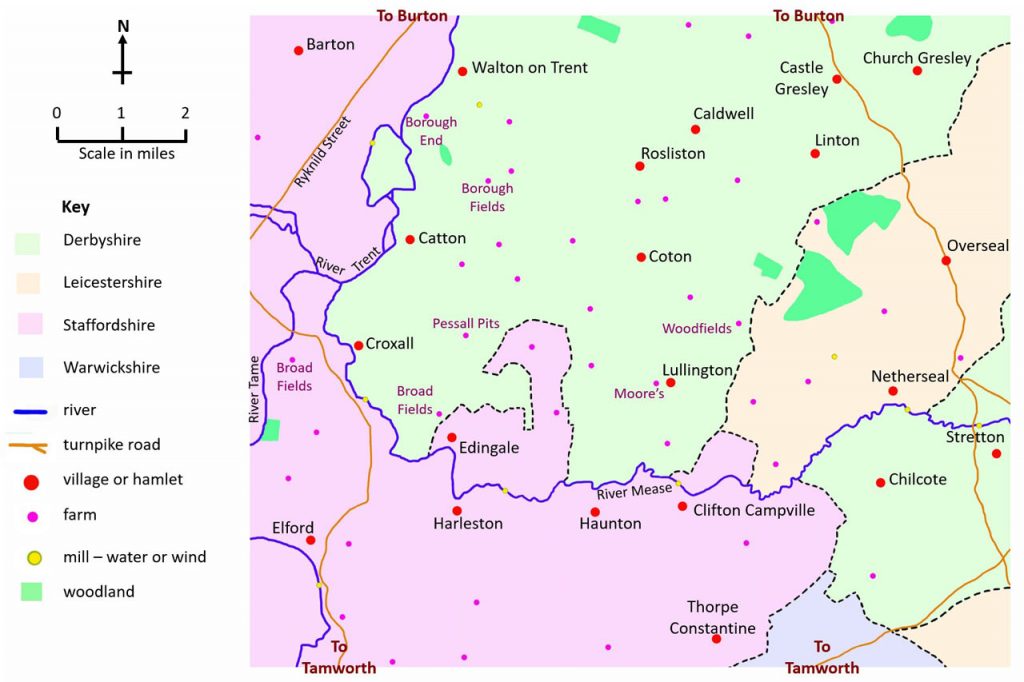

outside villages where these can be identified. Many farm buildings remained within villages. Named farms are among those

visited by John Farey in 1809.

Productive Farming within the Landscape

South Derbyshire’s open landscape with huge fields divided into strips, had vanished. Common fields at Lullington were divided into smaller units before 1633. And landowners at Walton-on-Trent agreed to enclose their common fields in 1652. Enclosure enabled farmers to use land more flexibly, especially for livestock.

Patchworks of squarish fields with hawthorn fences around their boundaries covered the area. Many farm buildings remained in villages, but Georgian houses appeared on holdings some distance away. These outlying farms with live-in servants, became small communities.

The Lullington estate formed larger farms in the 1760s, to increase efficiency. The outcome of negotiations created ill feeling which surfaced in hard times and polluted class relations for decades. Lullington’s largest farm gained an extra two hundred acres. One farmer with sixty acres became a labourer with two. Yet a farm with thirty acres remained. Losers in the process could rent a cottage plus a few acres with no obligation to pay the poor rate.

Fields tended to grow in size. On Mary Marlow’s thirty acres at Lullington, they were under four acres each. Yet an 1816 survey considered fields twice this size too small. Thomas Moore held 604 acres, and most of his fields were ten to twenty acres.

Landlords and Tenants

To make farms more productive, landlords and tenants invested capital. In the 1790s, the Croxall estate had at least one tenant at will, meaning either party could cancel the agreement at any time. Thomas Princep controlled most farms on the estate, owning their stock and employing bailiffs to manage seasonal routines. Thus, he provided all the finance.

To encourage tenants to invest, landlords offered greater security. Leases from seven to twenty-one years became common. As a result, both parties put capital at risk, though each sometimes felt the other should do more. Owners invested in land and buildings to increase rent. Tenants provided working capital to achieve higher profits.

Landlord Sir Roger Gresley received some £8,000 a year in rent from his South Derbyshire farms. At the age of 20, he imagined himself a fair man with correct views. A potential tenant who planned to populate the farm house with labourers and servants only, he dismissed. He rejected another whose personal life he considered peculiar.

Gresley leased 233 acres at Drakelowe to William Ward. Between 1811 and 1816, the rent increased by almost fifty percent. A surveyor thought Ward’s land bleak and his management adequate. He advised Gresley to improve the land and reduce the rent to £380 a year.

By February 1823, Ward was in arrears with his rent. He threatened to give up Warren Farm at the end of March unless Gresley lowered the rent. Gresley’s agent thought Ward’s management had slipped, and he advertised for a new tenant. No one offered what Gresley expected. John Cox agreed to take the farm, but only if Gresley improved the outbuildings. And Cox needed financial backing from his son, a draper in Burton-on-Trent.

South Derbyshire Farmers and Labourers

In a 1794 report on Derbyshire’s agriculture, Thomas Brown told the story of a farmer and his men who ate bread and cheese together at the kitchen table. They then said: Let’s go and do such and such a job. And off they went. Brown regretted the decline of this aspect of subsistence farming.

Relationships between farmers and labourers were close, though not always friendly. On smaller holdings, farmers worked alongside their men. Younger labourers, known as farm servants, slept in an outbuilding and ate in the farmer’s kitchen. This was convenient, especially for tending livestock. After the French wars, however, farmers paid lower wages and found live-in servants less economic.

In 1818, Lullington’s farmers introduced a system for the parish’s unemployed labourers. A man seeking work had to walk round the farms every day. At each place that refused him, he got his ticket signed. Only if signatures from all farms were on the ticket could he apply for poor relief. On the other hand, any work he found was rationed according to a scale agreed by all the farmers. This parish scheme was legal but harsh.

For Farey, labourers were almost invisible. Farmers acted and good husbandry happened. Thus, Farey saved readers from lengthy descriptions. He also drew a firm line between master and servant.

On a winter morning in 1818, two of William Ward’s male servants couldn’t start a new fire from the old. So, they seized a horn hanging above the mantelpiece. Then, one of them blew a live ember, while the other trickled gunpowder on it. Suddenly, the powder flared and exploded the horn with a bang. The blast felled a maid who stood in the doorway. In addition, the men suffered terrible injuries. One lost his hands, the other his eyes. The London Star expressed shock, plus sympathy for the wounded servants.

to the right and outbuildings to the left, is an unlisted building. Robert Lea’s family lived here in 1809.

South Derbyshire Farmers who Improved their Land

To increase profits, South Derbyshire farmers upgraded land. For example, Joseph Chell of Overseal tried to drain a flood plain for Eusebius Horton of Catton. Chell soon found himself on quick-sand, and had to sink wells eight feet deep. Constructed of brick, the wells conducted water into covered drains three feet below the surface, and from there to the river Trent.

At Lullington, Thomas Moore paid for a drainage and irrigation system on seventy acres of meadow adjacent to a brook. Moore rented Derbyshire’s largest farm. Invited into the kitchen, Farey noticed a rack for hanging boots with the tops downwards. Servants could see at once when they needed cleaning.

Irrigation could include manuring. At Borough Fields, near Walton-on-Trent, Robert Lea made temporary cuts from his farmyards into an adjacent field. By this means he sluiced rainwater, urine, and dung across eight acres. Perhaps he only ordered such work when the smell wouldn’t drift towards his home. After all, his daughter had won respectable friends with her social virtues. And Lea’s son married into the wealthy family at Borough End Farm.

To improve crop growth, farmers added lime to the soil. After growing wheat, Thomas Moore applied three tons of lime per acre. The exact amount depended on whether he carted it from Ticknall or Breedon. The latter was stronger, and could kill grass if used without care. Lime could also cause chemical burns, so labourers needed to handle it wisely.

Farm machinery

South Derbyshire farmers relied on dairy utensils and cheese presses, waggons and carts, ploughs and rollers. Harrows broke up clods of earth but, like other equipment, needed horses to pull them. Yet many tasks required hand tools. For example, sickles and scythes cut corn and grass.

Early in 1808, Pessall Pits farm, near Croxall, had five ploughs with support wheels. At Borough Fields, Robert Lea ploughed an acre and a half a day using a two-share plough drawn by five horses. The driver controlled the depth of furrows and guided the plough. He walked his horses steadily, turning them tightly on the headlands.

Many labourers threshed corn in the winter, removing grain from husks by beating the dry plant with flails. Yet threshing machines were available. For example, Thomas Noon of Burton-on-Trent obtained a patent for his design in 1805.

At Pessall Pits, new tenant William German spent £115 to install Noon’s latest model. It cost the equivalent of a year’s wages for four men. Depending on the crop, German harnessed three or four horses to a wheel. As they circled, they engaged gears which made the drum rotate two hundred times a minute. Fluted rollers struck downwards, threshing the grain.

Farey loved German’s machine because it improved efficiency. It also required fewer labourers. In a single day, it could thresh seven times more wheat than a man with a flail.

Born in 1784, William German took on the tenancy of Pessall Pits on 25th March 1808. A year later he married Mary Foster of Appleby Magna, but he died in 1810. His brother, John German (1791-1848), was born at neighbouring Broadfields farm, and worked it throughout his adult years. Many farmers had relatives who cultivated land nearby.

South Derbyshire Farmers and their Crops

Early nineteenth century farmers rotated crops on one area of ground over six to eight years. With no nutrient in constant demand, this practice strengthened soil fertility.

Crop rotation in 1800s South Derbyshire began with wheat or oats. Farmers then manured, ploughed, and let the soil rest from shallow rooted crops for a year. Instead, they sowed turnips. As these grew, labourers hoed between them. Thus, farmers cleared the land of weeds and gained winter fodder for livestock.

In hard frosts, labourers couldn’t collect turnips. So, Thomas Moore planted ten acres of cabbages. As an alternative root crop, he tried carrots. These sunk eighteen inches into the red marl soil, and most grew no thicker than knitting needles. After a root crop, many farmers sowed corn again.

Next in the rotation came a mix of clover and rye grass which formed cultivated meadows for several years. Joseph Smith of Woodfields, Lullington, thought worm casts injured his meadows. So, he scattered dry barley chaff. This stuck to the worms when they emerged. Unable to return to their holes, rooks devoured them. Farey thought this a little random. Farmers should deploy a team of ducks to do the work.

South Derbyshire farmers distinguished between cultivated meadows and those alongside brooks or rivers. Many thought the latter gave better cheese.

Towards the end of their crop rotation, farmers sowed beans or oats. For example, Moore drilled five acres of beans in 1809. His labourers distributed the seed by hand, opening and filling the drills with spades. Moore reckoned this cost him nineteen shillings an acre.

South Derbyshire Farmers and their Animals

A sale at Pessall Pits in March 1808 included thirty cattle, a hundred sheep, and ten horses. Many farmers visited by Farey bred livestock to meet current trends in food or labour. However, some still used oxen to draw waggons or machines.

On his farm near Loughborough, Robert Bakewell had developed a methodical approach to breeding sheep, cattle and horses. Many followed his example. Thus, two Lullington farmers kept stallions of a type improved by Bakewell. They leased them to serve their neighbours mares. These gave birth to stout, black horses to pull ploughs and loaded carts. However, farmers used other kinds of horses for sport and leisure. When Francis Hamp of Walton sold his well-bred horses in 1813, one was a castrated bay for gentle riding and another a brown horse for riding or pulling a carriage.

Farmers also kept pigs and poultry. For example, Thomas Moore’s white boar at Lullington was broad in the back, with short legs. He charged his neighbours seven shillings for each sow it served. Moore fed his pigs cooking slops and whey from his cheese pan, supplemented with oatmeal. At fifteen months old, they weighed 320 pounds. Each year, he killed up to seventeen for family use.

One significant local breeder of livestock was Thomas Princep who inherited the Croxall estate in 1795. Its farms covered at least 1,450 acres. High Sheriff of Derbyshire in 1802, Princep was a bachelor who lived in an untidy-looking Elizabethan Hall, more farmhouse than gentleman’s residence. Inside, paintings of his father’s famous livestock covered the walls.

Cheese and Beef Production

Princep refused to tell Farey the origins of his cattle. Farey then asked: Which breed of cows produces more milk? Princep’s reply made little sense. He made a vague observation about a dairy of cheese. In his report, Farey made a point of showing up Princep as awkward.

Using a breed of cow developed by Robert Bakewell, Princep and his father made adjustments. Initially bred to maximise beef production, it’s milk yield was relatively low though high in fat. One Princep new long-horn butchered in 1786 at Lichfield market weighed 1,550 pounds. Across the top of its ribs lay seven inches of fat.

The Princeps named their new long-horns: Shakespear, Bright Eye, Razor Back, White Lupin. And they could sell them for high prices. In 1808, Princep refused £525 for a bull and £105 each for thirty cows.

Princep lost many one-year-old cows to black-leg. This disease released gas in the muscles of well-nourished calves. The swellings, when rubbed, rustled like dead leaves. No one could cure the infection, but Princep believed he prevented it. During March and April, he bled his calves once a fortnight. He also fed them salt and potash dissolved in human urine. Many farmers adopted similar recipes.

At Lullington, Thomas Moore had a large dairy herd, consisting of new long-horns plus a cross between long and short-horns. He reckoned each cow gave 340 pounds of cheese a year.

William German of Pessal Pits kept short-horns and old long-horns for milk and cheese. The latter was Derbyshire’s most popular cow before 1800.

When Robert Lea’s cows became barren, he fattened them on grass. As soon as they weighed about 800 pounds, he sent them to the butcher. By 1810, fatty meat no longer pleased genteel tastes. However, butchers still sold animal fat to make tallow for candles.

Sheep for the Slaughter

In 1770, Robert Lea of Walton hired a ram for £31 to serve his ewes. It came from a flock of New Leicesters at Dishley, developed by Robert Bakewell. In the 1800s, Thomas Princep’s rams served Lea’s ewes. When first sheared, Lea’s sheep produced five pounds of wool apiece.

By 1790, many wealthier farmers in southern Derbyshire kept New Leicesters. These were so finely bred for fatty mutton, however, their hair grew thin. Farmers gave them linen caps to protect them from flies. As a result, breeders strove to develop thicker wool into the breed.

Princep hired rams from Leicestershire’s foremost flocks, and let his own to local farmers at £52 each. He exhibited one of his three-year-old ewes at Lichfield Fair in 1805. When butchered, and with the offal removed, it weighed 220 pounds, twice the weight considered optimal today.

In the 1760s, Thomas Moore’s father formed a pure bloodline of New Leicesters from the flock of a Nottingham breeder. After Moore senior’s death in 1810, his son William took over at Thorpe Constantine while Thomas remained at Lullington. Both men valued their flock’s pedigree. Each September Thomas had forty rams to let, mostly for farms near Daventry, 45 miles to the south. In addition, he maintained a flock of 220 ewes.

Thomas and William Moore

Whether formally partners or not, the businesses of the Moore brothers were linked. William was a seedsman, grazier, trader in cheese and general dealer. In 1819, aged 45, he sold his entire farming stock, claiming ill-health. Even his silver plate and chinaware had to go. Also in trouble, Thomas advertised his prize sheep for sale.

The brothers’ financial difficulties had several causes. In January 1819, Lullington’s vicar won a court case against Thomas and demanded £1,200 for arrears in payment of tithe. However, the depressed state of farming which followed the Napoleonic Wars was of greater significance. After 1818, the market for hiring well-bred rams rapidly declined. The Moores probably over-invested in this side of their business.

Cultivation of Thomas Moore’s land dropped. Neighbouring farmers came to his aid, offering labour. Perhaps he’d helped them in the past. Possibly they identified with his situation. Whatever their reasons, on 4th April 1820 Moore had six teams of horses at work on his land, in addition to his own. A greater number supplemented his efforts the following day.

Moore turned to family members to guarantee payment of £1,000 in rent. An uncle agreed, but had a stroke and died. So, Moore approached his brother-in-law at Haunton. Edward Baker signed the required legal papers and then tried to get out of the agreement. When Baker failed, he got permission to draw up an inventory of Moore’s possessions. Moore felt cruelly treated. In a letter to his landlord, he explained his situation. He promised to double his efforts to benefit the farm.

In 1820, William and Thomas Moore became bankrupts. Creditors thought William had illegally conveyed land to a close relation. They acted to recover £4,500 plus an estate near Birmingham. For reasons now unclear, the case dragged on for years. Creditors received no dividend from sums recovered until 1833.

The Law saw bankruptcy as a misfortune but acted against people who owed money. The Moore brothers probably went to a debtor’s prison.

South Derbyshire Farmers: Concluding Comments

Farey gave a partial view of farming in the early 1800s. Many farmers rejected methods he favoured, and spurned the rearing of prize animals. In Farey’s account, New Leicester sheep appear as South Derbyshire’s dominant breed. On the ground, many local sheep were of uncertain origin.

Tenants and landowners invested capital to improve productivity. Men like Thomas Moore did not simply earn a living from the land. Moore was also a dealer, taking financial risks. He needed to keep his eye on the market for fluctuations in prices and general trends.

Intensive agriculture increased risk. Farmers could misread the market or extend their operations too far. Crops sometimes failed, or disease wiped out a herd. Each week, the Derby Mercury listed England’s bankrupts. Yet, despite their anxieties, farmers could be neighbourly and charitable. For example, at the end of a good harvest in 1795, Thomas Princep sent a load of fine wheat to Lichfield market to sell cheaply to poor families.

As a village’s chief inhabitants, farmers had considerable influence on employment, administration of the Poor Law, and other community issues. The imposing Georgian fronts of an increasing number of farmhouses reflected their growing wealth. However, at least one side of these buildings spoke of their working lives, their care of livestock and storage of agricultural products.

Many farmers achieved respectability but were not gentlemen in the traditional sense. Of course, there were exceptions. Thomas Princep owned an estate but involved himself in the business of farming rather than receiving income from rent alone. In a class-conscious society, most farmers occupied a middle management role within their communities.

Next: You may enjoy a Four Shires History article about John Prior, a middle class mapmaker of eighteenth century Leicestershire.

Leave a Reply